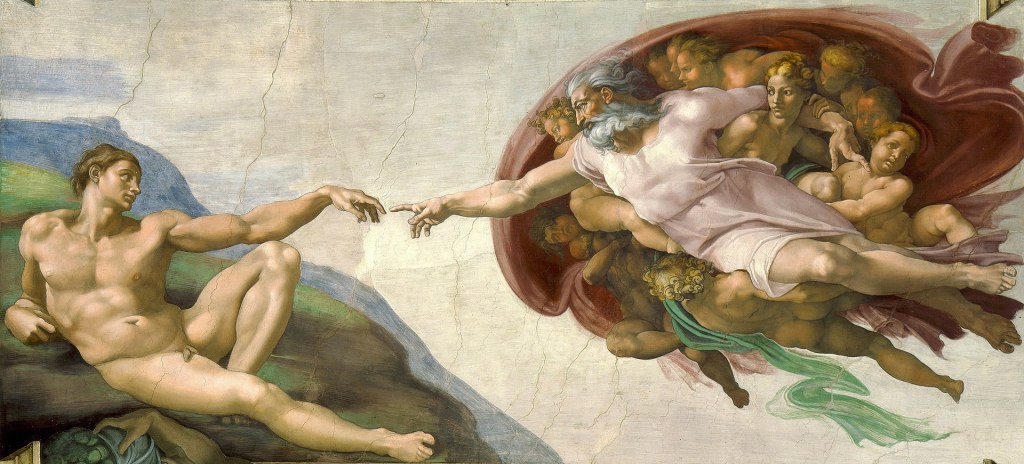

This very familiar painting, The Creation of Adam, by Michelangelo, has a fascinating history behind it and a deep theological revelation within it.

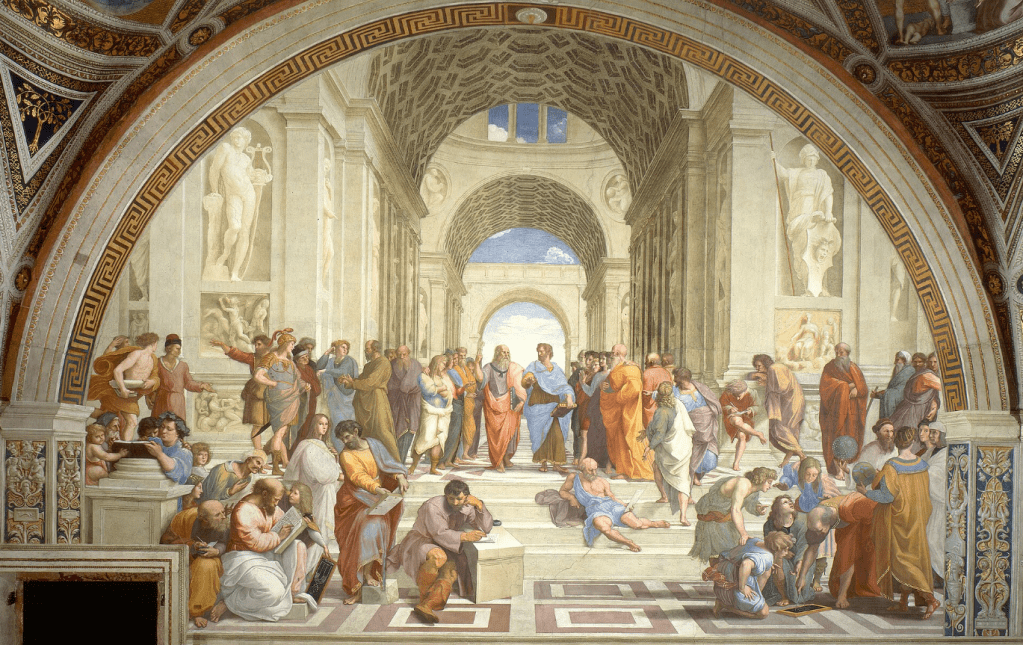

The Sistine Chapel, in Vatican City, was completed in 1483, and since has been used as the chapel for the Pope to hold special worship services. We are most familiar with one of the scenes from the ceiling, depicting the Creation of Adam. What’s first and most significant about the painting was that it was without precedent. No one had done anything on this scale before. This is to painting what the first TV was to video. The ceiling was commissioned by Pope Julius 2 in 1508, and the Pope made certain specifications about what he wanted – originally the 12 apostles. But Michelangelo demanded freedom to do what he wanted, and instead painted a story of salvation, from Creation to the fall to Noah and the flood. Around those are the story of the Old Testament and the prophets, because they forecast the coming of the Messiah, leading to the Last Judgment. Around the lower tier are a series of tapestries of New Testament figures created by the legendary painter Raphael. Botticelli did one of the scenes as well.

Now what’s most engaging about this particular panel of the ceiling (I mean, after Adam says, “Hey, eyes up here”), is the musculature of the hands and the expressions on the faces. God’s hand is stretched, extended. He is leaning forward. God is desperate for this connection. God wants to reach to Adam. Adam is leaning backwards as casually as if he were watching YouTube. And yes, he may have stopped on the 700 Club channel for a minute, but he doesn’t seem that interested. His hand is extended a little, but it’s dropping. He’s unconcerned. This is not critical for him. Do you see what Michelangelo is telling us theologically? Our relationship with God is his doing, not ours. It is by grace because he loved us, and not because we deserved it, and not because I was a generally good person in this life, and not because I made the right decision. Dead is dead.

Ephesians 2 tells us that we are “dead in our transgressions and sins.” But verses 4 and 5 give us the great promise: “But because of his great love for us, God, who is rich in mercy, made us alive with Christ even when we were dead in transgressions—it is by grace you have been saved.”

Michelangelo teaches us that without God’s activity, we are lost, not in malice and rage, but in apathy and lifelessness. All the energy of Creation and salvation are God’s work.

We are then set free to life, to real life, to life on Jesus’ terms. We rise from apathy to adventure.

I once knew a guy who said that he wasn’t going to donate to charity until he was older and got rich. He told me, “I can give so much more if I wait until I have a lot.” You know what’s going to happen? That guy’s never going to give anything. He won’t develop the musculature for it. He’s just going to atrophy. That’s like saying, “I’m going to go to the gym when I retire. Right now I’m too busy with work and kids and stuff. But when I finally retire, then I’m going to get in shape.” You’ll be lucky if you make it to retirement like that.

When we set out to follow Jesus, it is to join the passion of a life lived in love, in self-sacrifice, in generosity, in care for the desperate. We move from spectator to player. When we follow Jesus, we leave behind stale religious attendance, and we become the priests and missionaries. With Jesus, the call is not to complacent intellectual assent. When we follow Jesus, we rise to life.

Here’s a painting that’s changed the world.

Here’s a painting that’s changed the world.