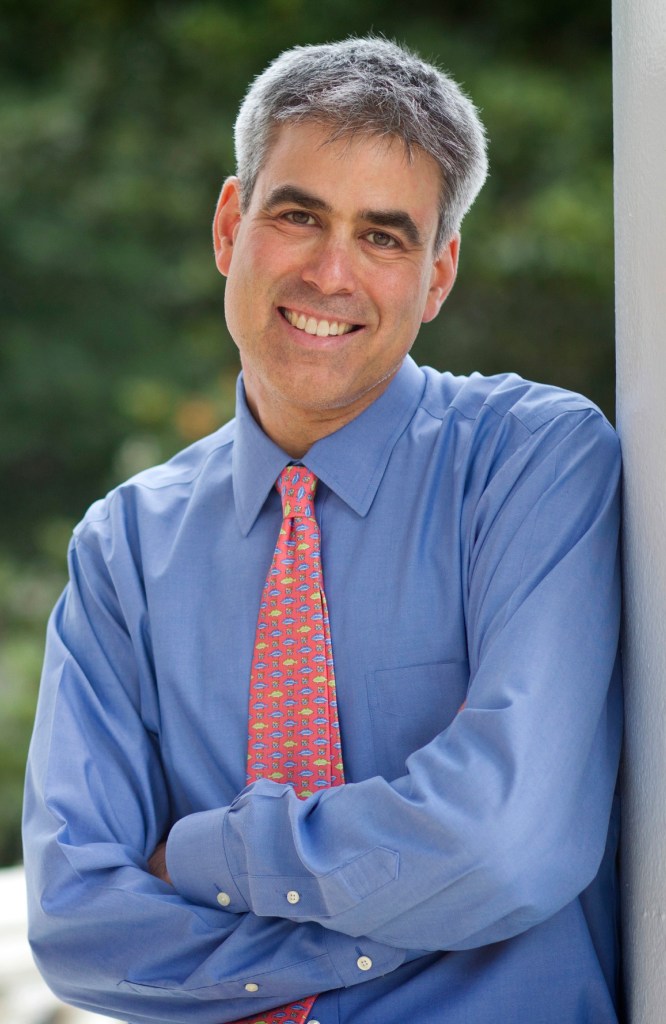

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt likes to play a trick on crowds. He’ll ask an audience, “What does it feel like to be wrong?”

“Embarrassing,” someone will answer.

“Frustrating!”

“Confusing!”

“No,” Haidt will correct them. “You’re describing what it feels like to find out that you’re wrong. What I asked was ‘What does it feel like to be wrong?'” And the correct answer is – it feels exactly like being right.

When we are wrong, before we are aware that we are wrong, we assume we have things figured out, that we see reality for what it is, that our minds are clear and our heads are screwed on straight. The only way to discover that we have gotten off course is through dialogue and interaction with people who see the world differently than we do, with the humility to admit that we still have things to learn.

When we surround ourselves with people who only see the world in the same way that we do, we insulate our wrongness. We are surrounding ourselves with people who are wrong in the same way that we are, which puts us further from the opportunity to discover the truth. There is now a wall of wrong supporters standing between us and veracity.

A refrain that is being chanted by conservative Christians in America today is that truth is under attack from deceivers who will profit from the mass distribution of lies. After all, there is a war on Christmas, a propaganda machine being run by medical elites, and a secret cabal of blood-drinking pedophiles in the highest levels of government. One news network has even had to pay three quarters of a billion dollars for knowingly propagating false information. To this worldview, truth is like a delicate flower at risk of a malicious cultural lawnmower.

But is that true of truth?

In my experience, truth is less like a flower than a weed. It’s persistent, it crops up after you think you’ve removed it, it not only upturns dirt, but it can crack concrete, and there’s always another generation of it waiting to replace the last. Perhaps truth is more infectious than its would-be defenders suppose.

At one point, humanity tried to crucify embodied truth, and that only lasted for three days.

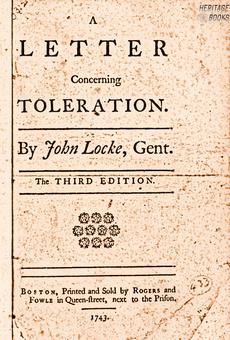

Philosopher John Locke in his 1689 Letter Concerning Toleration wrote, “The toleration of those that differ from others in matters of religion is so agreeable to the Gospel of Jesus Christ, and to the genuine reason of mankind, that it seems monstrous for men to be so blind as not to perceive the necessity and advantage of it in so clear a light.” Locke’s work became foundational to modern democracy, especially American democracy, and particularly his biblically defended case for religious toleration and free speech. If the First Amendment had footnotes, they would all reference Locke’s writings. I would argue that as we campaign to cancel our competitors, we are taking the Constitution out of the hands of those who inspired and wrote it.

So rather than the winner-take-all polarization towards which contemporary American political culture (and consequently religious culture) is barrelling, we might want to pause to consider that we may need a diversity of opinions to keep us learning, that civil society may require humility more than conquest, and that, in the end, it may turn out that our enemies were partly right.