Watching the sun set over the ocean always feels like the closing curtain to a good play. Moments like these feel like a sweetly passing sentiment, because we have become so used to God whispering his love that we take it for granted. We don’t even hear it, a spouse’s “What was that?” to the other who has already left the room. But the order of the universe is in fact a message from God.

The harmony of creation is a lullaby from a God who is reordering a broken world. It’s his way of telling us there is still sense in things, even after tragedy. It’s the strength of the arms that cradle us. It’s his, “There, there.” Because there is fundamental order “out there,” maybe one day I can have it “in here.”

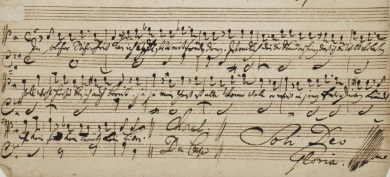

And thus you can hear the love of nature’s harmony in Bach’s Inventions. He scratched at the top of his compositions, “SDG,” or Soli Deo Gloria: to God alone be the glory. If he had not written it there, his music would say it by itself, because the fundamental order that beauty captures glorifies God. SDG is written on the sunset. The pulsing rhythm of sunrises and sunsets are a visual drumbeat.

Creation’s order plays on our natural love of harmony and structure. That should be a clue to us as to where we come from. The idea that order could just spring from a primal nothing should strike us as absurd. Order has to have come from somewhere. At least when a magician pulls a rabbit out of a hat, there was a hat. For those who believe the universe just came to be, there is no hat, and no magician. Science has changed its mind on this one. Historically, the predominant view was not that the universe came to exist, but that it had always been. For those who didn’t believe in a Creator, the idea of a moment of creation was too much of an affront. In fact, Marcus Aurelius called it logically absurd.[1] “Out of nothing, nothing comes.” Today, we know universally and conversationally about the Big Bang, or in other words, the magically appearing rabbit. And this fact honestly makes atheists queasy.

Ludwig Wittgenstein described what this feels like. He said that he sometimes had a certain experience which could best be described by saying that “when I have it, I wonder at the existence of the world. I am then inclined to use such phrases as ‘How extraordinary that anything should exist!’ or ‘How extraordinary that the world should exist!’” [2]

And it is extraordinary. Extraordinary that our hearts long for order. Extraordinary that we feel like it should be more complete than it is. And extraordinary that our deepest longings jibe with that which God has promised. God is a fairly sloppy artist. He’s left his fingerprints all over the work.

1 The Meditations of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, V.12.

2 Norman Malcolm, Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir (London: Oxford University Press,1958), p. 70.